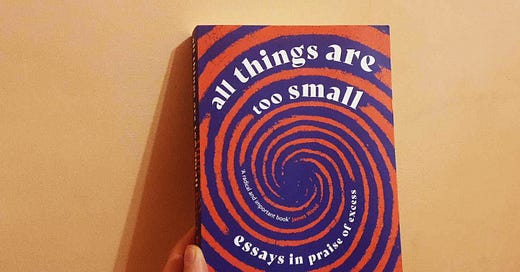

Becca Rothfeld has faith in desire. All Things Are Too Small, the debut book from the Washington Post critic, takes on various forms of asceticism, minimalism and traditionalism, with their urges towards managing if not suppressing the pursuit of our desires.

In a time where leftist idea-mongering often seems as inspirational and attractive as an unexpected memo from your HR department, this is a rich and challenging book. Less is more, the saying goes. More is more, says Rothfeld — more art, more thinking, more sex, and not just in terms of quantity but in terms of ambition. All Things Are Too Small is the literary equivalent of a paint bomb thrown into Marie Kondo’s living room.

There is much to agree with here, but to reduce the book to its good and bad arguments is to miss the point. One of its enemies — and one I share — is excessive instrumentalism. So, I should be clear that the book is, for the most part, a pleasure to read — funny and poetic. “Each night for a week, I lay awake in my stagnant bedroom…” Stagnant bedroom. Two words can evoke a lot.

Rotheld incisively defends the personalities of places from minimalists — and then the personalities of people from the cognitive minimalists of the “mindfulness” trend. “Pure awareness has no interests, tastes, desires, or attachments,” she writes:

… and yet these are the bases on which human decisions are made. From the alpine vantage point of mindfulness, if we could ever reach it, all our pursuits back down on the ground would look equally ridiculous, as senseless as the bustling of insects.

And a mountain, viewed from space, is no more than a blemish. Truly, there is nothing that serene detachment cannot render trivial — though I would be far more sympathetic to its advocates if they tended to pursue religious experience rather than an optimal approach to maximising annual sales.

An essay about the dark transformative power of love, “The Flesh, It Makes You Crazy”, is very striking. “Being in love means you are completely broken, then put back together,” sang Jason Molina on “Being In Love”. Here, you can be put back together into a Cronenbergesque monstrosity.

The distinction between “more” and “less” is not always helpful, of course. One can have too much of bad things and too little of good things. In an essay on desire and consumption, Rothfeld writes:

The thirteenth-century canoness Julia of Cornillon told nurses and family members who entreated her to eat that she was saving herself for “better and more beautiful food”. Aren’t we all? But until we ascend to that celestial restaurant, I recommend bingeing to bursting. If it is never enough, try to love that about it. Try to savor the slivers of salvation hidden in all that hideous hunger.

She doesn’t just mean food, of course, but I’ll stick with everyday examples. I love smoking. I really love it. Cigarettes relax me like almost nothing else. But I know that being a full-time smoker would diminish my other pleasures. Running would be painful (and not in the right way). Food would taste less good. My familial history suggests that it would curtail the pursuit of longer term desires.

“When we say,” asks Rothfeld:

“She wants to have her cake and eat it too,” what crime do we allege? Do we blame her for the daring of her appetites, or for her failure to sate them?

I don’t blame her for anything. A factual claim need have no moral implications, and, with apologies to Mark Fisher, I don’t think “realism” is a dirty word. Desire needs order — not just to protect us from its hazards but to give all of our desires a fighting chance of being fulfilled.

The most provocative chapter for right-leaning people, “Only Mercy”, addresses sex — defending sexual liberalism from its modern critics. Rothfeld’s prose is so elegant that her criticisms can look more damning than they are. “On the one hand male misbehaviour is biologically ingrained,” she writes, sneeringly, of Louise Perry’s The Case Against the Sexual Revolution and Christine Emba’s Rethinking Sex, “On the other, pornography is what drives men to acts of exploitation.” On the one hand, a pitbull has an innate tendency towards aggression. On the other hand, poking it while it’s asleep will actualise that tendency. I think the utilitarian case against pornography is weaker than its advocates believe, but where is the contradiction here?

Rothfeld’s faith in the clarity of desire is excessive. I’m not much of a social conservative — not least because I’m childless and unmarried — but I don’t think the conservative argument tends to be that desire is bad, though it can be, but that it can make incompatible demands. We desire short-term freedom and long-term fulfillment, and while there is no necessary contradiction here, there can be one. People end up wishing, for example, that they had entered a room after the door has closed.

The essay makes the valid point — in the context of kink — that desires which are innate and desires which are socially mediated can feel as powerful. True. But what seems like one desire can contain multitudes. In sex, for example, people can desire each other. But they can desire someone else, or the sense of being someone else, or the admiration of others, or the cathartic degradation of others. Those desires are real too, but they are not equal. They can run, at the same pace, down very different paths.

Still, good points are made. Rothfeld is correct that right-leaning commentators can instrumentalise sexual and romantic relationships to excess. We say that having children is important because we need security in our old age, for example, or that marriage is important because we need companionship when our energy and appearance have declined. But how many of us apply that to ourselves? I don’t want marriage because I want someone to hang about with — I want to love and be loved, and powerfully enough that love endures even as the rest of us is withering away.

Rothfeld also makes an effective argument that right-leaning critics of the sexual revolution have no positive model of sex except as something which serves other purposes — strengthening relationships and forming children. Certainly, to imply, deliberately or accidentally, that something which occupies our attention to such a vast degree does not have its own tremendous innate significance would be limp indeed — empathetic though I am to the sense of embarrassment that can preclude detailed analysis.

But there’s at least some extent to which embarrassment should be resisted. We should praise desire — in the face of apps which turn romance into some sort of distant cousin of corporate hiring procedures, and in the face of pornographic platforms which atomise and sterilise romantic and erotic instincts, and in the face of the dehumanising gifts of artificial intelligence. Asserting the richness of the human imagination is a vital task in the face of machinic power. This does not mean praising desire in all of its forms, but to speak in praise of fire is not to defend arson.

So, for all I disagree with the broader prescriptions of All Things Are Too Small, the implicit exhortation to intensities of thought and feeling strikes a chord — or, perhaps, a “Creep”-esque dissonant blast.

It sounds like this book tendentiously tries to unite a bunch of disparate things the author doesn’t like under a fuzzy concept of “less” so she can criticize them under the equally vague banner of “more”. She’d be better off just writing separate critical essays on minimalist interior design and sexual conservatism rather than straining to find a thread linking the two. There isn’t one.