Just after 11pm on August 12, 2019, 16-year-old Alex Smith was walking home from a dinner with friends when he was spotted by six men who were out to kill. Smith was chased on foot across the Regent’s Park Estate in Camden, where he banged on doors and begged for a place to hide. Nobody helped him. The men caught up and stabbed him to death. Witnesses claimed to hear them “screaming and laughing”.

Two men who had chased, although not stabbed, Mr Smith were caught and convicted. Another was convicted of burning their cars. The remaining members of the gang were believed to have fled abroad.

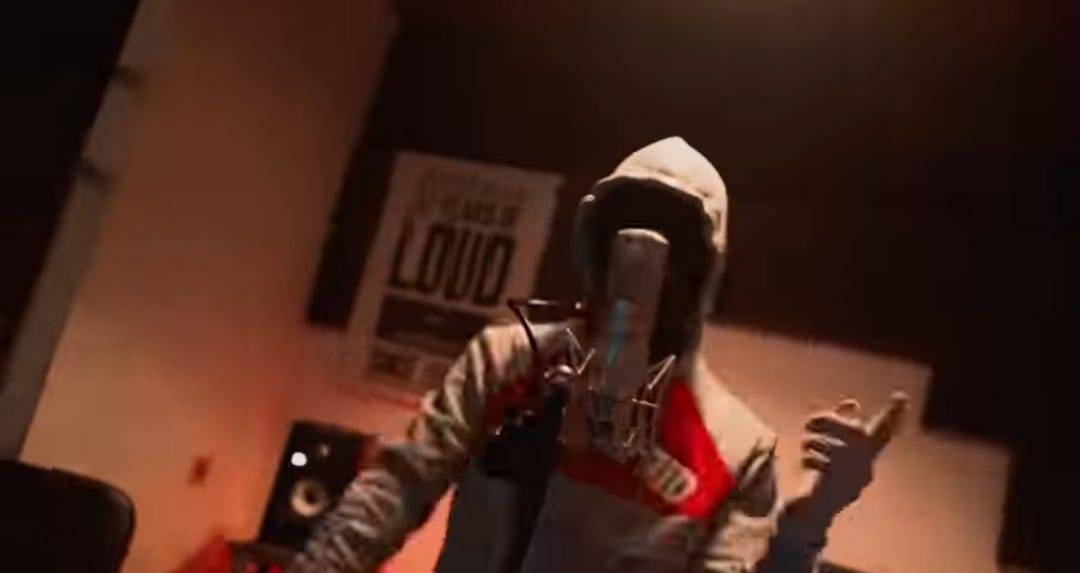

In 2020, a Camden rapper started to create a lot of buzz in the “UK drill” music scene. Calling himself “Suspect”, he had the morbid lyrics that fans of the dark subculture enjoyed. “Same place we used to play run outs is same place his chest got dug out.” “No half heart ching, I'm pushin’ it all in/Exit wounds when I get to the borin’.” “Couldn’t get plugged into a life machine/‘Cah he died on scene.”

Easy to dismiss as products of the imagination, perhaps. After all, how many death metal bands have actual murderers in their ranks? (Some, granted — but not most.)

Yet black metal fans appreciate fantasy. Drill rap fans appreciate realism. Online chat around the genre strongly implied that Suspect was one of the murderers of Alex Smith and was now residing in, and performing from, Kenya.

He was hugely popular. Many of his songs have millions of views on YouTube. He has — a year after he was forced to stop releasing music — about half a million monthly listeners on Spotify. This was without any mainstream promotion.

Nor was he alone. The rapper “2Smokeyy”, using the same “Active Gxng” brand as Suspect, released the song “Knock Down Ginger”, which included the words:

R.I.P, I mean laugh out loud

Yo Culprit, bye-bye

Silly boy try play Knock Down Ginger when he shoulda called up 999

As you’ll recall, Alex Smith was knocking on doors as he fled.

Gang violence has been a blight on Camden for years, with gangs from the Peckwater and Queen’s Crescent estates feuding with gangs from Agar Grove (to which Suspect belonged). In 2018, two men were brutally killed in a single night. Later, a music video advertised as the product of Peckwater members showed the mugshots of the convicted murderers as a rapper spat:

Hella members locked, stuck in the box

Still wanna step and purge and pressure

You ain’t ever stabbed someone and felt better

Then feel like shit ‘cause you heard he ain’t dead

Earlier this year, a funeral for a mother and her daughter in Camden was sprayed with bullets. Three young men have been arrested after six people, including two girls, were injured in an incident that seems almost certain to have been gang-related.

“Suspect” became a cult figure online. Rumours abounded that the police had dropped their investigations into his part — or lack thereof — in the death of Alex Smith and that he had returned to England. Much of the appeal of drill — as I have written before — is wrapped up with gossipy online chatter about who stabbed who, and who shot who, and whether people are going to be convicted.

This is not a new phenomenon. Organised crime has been the subject of fevered speculation for decades. There are people who know more about John Gotti than their mums. Still, at the risk of ennobling the very much ignoble work of the mafia, the sheer senselessness of gang violence in Britain, and the sheer youth of the young men involved, make the drill scene exceptionally morbid.

Tariq “Suspect” Monteiro was arrested in Kenya in 2022 along with his accomplice Siyad “Swavey” Mohamud. His album, Suspicious Activity, was released days afterwards and was a tremendous success. The last song, “Thrill”, featured the lines:

Ever sit down and smoke your spliff like

“Fuck, I did some fucked up shit.”

And the fucked thing is you love that shit

You won’t understand ‘til you take that risk

Monteiro and Mohamud went on trial this April, with fans online hoping and praying that they would be acquitted. It was not to be. Both were found guilty and sentenced to more than twenty years in prison.

On one level, the appeal of drill is musical. Dark, restless soundscapes and fierce lyricism — like various forms of rap and metal before it — direct strands of fear and rage into a whirl of energy. The Guardian’s Ciaran Thapar was not wrong to link it with the concept of catharsis. Dark music can purge buried negativity.

On another level, though — and a more consequential level — it concerns the past and future killings of young men. Of the five drill rappers I would have considered most talented, two are awaiting trial for murder, one seems to be awaiting trial for attempted murder and two have been convicted of aiming guns at the police. A quick tour of other leading figures of the genre throws up various examples of young men in prison for murder, drug offences, gun offences, kidnapping et cetera — and a lot of young men who have been killed. Almost no one actually escapes crime through music — that romantic fantasy — because to reach fame is to have been so heavily invested in violence that people want to kill you, or the police want to jail you, or you’re so hate-filled that revenge counts for more than being free.

It is hard to draw a direct link between music and violence. Gang wars existed long before the genre. Monteiro — like “King Von” in the United States — launched his rap career after killing Alex Smith. Still, I don’t think it’s ridiculous to wonder if there is a sense in which the genre acts as a honeypot for young men liable to be drawn into criminal gangs. Certainly, it would not be ridiculous to wonder if known women beaters singing about beating women might encourage women beating. It wouldn’t be the main cause, but it could make things worse.

It’s tough for the families of the victims involved as well. I’m not the most sensitive person to “problematic” language but knowing that hundreds of thousands of people are rapping along to lyrics about your son’s death must be hard to bear.

Still, what also interests me is the relation of the genre to what I have called “vicariotica”. The more drab and safe our lives become — the more bounded in terms of our relations and our opportunities — the more that some of us have gravitated towards consuming media that portrays extremes of human experience — extremes of consumption, and sexuality, and violence.

People — not all people, but people, and especially young people — feel excitement through others, and radicalise their consumption in search of unattainable fulfilment. Most of them would never kick let alone stab someone, but inhabiting the mental space of somebody who would sharpens the dull edges of their élan vital. How else to explain a senseless Camden murder entertaining millions? True crime is one thing but hearing it from a killer’s mouth is something else entirely.

Vicariotica(* might prove more genre-fluid as it were, to serve as a broad umbrella term for disparate phenomena well beyond music scene 😊 I hear unmissable echoes from much less gruesome context ↓↓

🗨 My hunch is that somewhere near the heart of the problem is the fact that the pursuit of honour is really, *really* important to a great many men [...,] and that this remains true even when the only emotionally satisfying place to pursue honour is within a simulacrum.

reactionaryfeminist.substack.com/p/incredible-shrinking-men

--

(* ‘tis a word good to know 👌 (h/t Maurice Sendak, images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/58efb4b944024397c4e0e330/1508506597192-2ZTHD2SSJCCOET8Q1BME/Maurice+Sendak+2.jpg)

Me and Rishi don't live in Cambden so it's all good.